Men's Early 15th Century Cote

This is the last post about my entries from the Kingdom of AEthelmearc's Arts and Sciences Pentathlon at Ice Dragon, but fear not! I have more projects in the works that will appear here soon!

This garment is a man’s houppelande or cote. This style of garment gained popularity during the late 14th- early 15th century in England and France. It is essentially a baggy outer layer constructed in a way to create large loose waves of fabric. It is often seen belted at the waist, which accentuates the pleated appearance around the body. The sleeves styles of these garments vary from utilitarian and straight to extravagant and flowing.

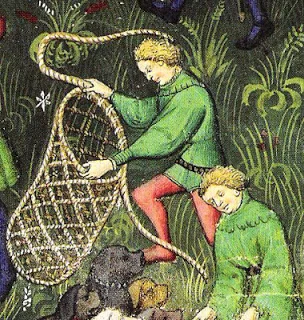

My goal was to create an outer layer piece of clothing for a spring or fall season that is appropriate for a noble in an everyday setting. I wanted the sleeves to be stylish, but not cumbersome so I chose a bag sleeve with a fitted wrist. The primary images I referenced for visual inspiration come from the Hunting Book of Gaston Phébus and the Chroniques de France ou de St Denis. In order to achieve the desired fullness in the body, I created a pattern combining a two existing theories.

Design

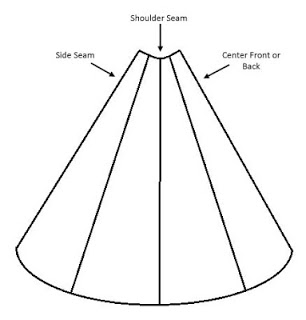

The pattern I created for this garment is a combination of two theories on constructing a houppelande. I liked the orientation of the shoulder seam Cynthia Virtue used in her pattern. This gives the garment the desired fullness falling from the shoulders, however, as medieval fabric commonly much narrower than modern cloth I did not want to make quarter circle sections from a single modern width of fabric. Gores and gussets are a staple of medieval clothing construction and using some variation of panels to create a full houppelande is a logical solution.

I found an image of an extant houppelande from Czechoslovakia dated to 1396. I also found a webpage by Master Jack Baynard (as known in the SCA) with a line drawing of the pattern that had the top of the panels oriented to the neckline. The shoulder seam is formed from the side panel only. There was no citation for the article Master Jack references so I was unable to verify his conclusions, however, they seem logical. I decided to use panels similar to Master Jack, but I oriented the panels so they meet at the shoulder seam similar to Cynthia Virtue’s design. I also curved the shoulder seam to give some extra fullness when the seam settles on the wearer.

My pattern for one quarter of the body. The pieces are actually right triangles. The neckline of the garment is a V-neck with a collar. This style of neck is seen in Hunting Book of Gaston Phébus. A back view with seam lines can also be seen in Chroniques de France ou de St Denis. Designing the body to have the angled panel at the center front and back with the panels meeting at the shoulder seam created the V shape naturally. I pieced the collar together after the main body of the garment was finished. The front and back pieces are slightly different to achieve the correct fit, but the result is similar to the image below.

The sleeve pattern I designed myself. The sleeves are cut in a ‘bag’ shape with a close fitted wrist. I wanted a sleeve with a tight, buttoned wrist. I designed the seam to run along the back of the arm around the elbow (similar to the placement of the seam on the Charles de Blois sleeve) in order for the buttons to fall at the outside of the wrist instead to the underside of the wrist. This allows the wearer to remain comfortable when resting their arm on a table – the buttons will not press against the arm. To achieve the proper drape for the bag part of the sleeve with this seam placement, the pattern ends up looking like the image below. There are three pieces, two traditional ‘bag’ shapes and a thin section that sits on the top of the arm. This extra piece gives the desired fullness seen in the extant images as well as good placement for the buttoned sleeve.

Materials

I used navy blue wool 2.2 twill for the outer layers and natural tabby woven linen for the lining.

Tabby woven ivory silk was used for lining the collar and facings at the wrists and armholes. Silk linings have been discovered as facings on garment fragments with button holes as well as curved sections believed to be a neckline or armhole.

Linen and silk thread were used to construct the garment. Beeswax coated linen thread was used for all interior seams and silk was used for facings, visible seams, and finishing.

The linen thread is a natural beige color. This would have been a readily available thread in the early 15th century and when coated with beeswax, very strong. Only seams not visible from the outside of the garment used linen. A navy blue filament silk thread was used for all stitching visible on the outside of the finished cote.

Construction

The main seams of the garment were all sewn with a running stitch, stab stitch, or hemstitch. The linen sections were folded over and flat felled to prevent fraying. The silk pieces were always folded under to secure the raw edges. The wool seams including hems are all single fold as the qualities of the wool would prevent severe fraying.

I washed the wool before construction in order to achieve a fulled fabric that would not fray easily. The buttonholes were creating by cutting a slit in the fabric and binding the edge with a buttonhole stitch.

I used 16 panels total, 8 for the front and 8 for the back, with a center seam at the front and back. This seam allows for the panels to join at the shoulder seam and form an easy V-neck as previously discussed in the Design section. I sewed sections of 4 panels together at a time until I had front right, front left, back right, and back left sections of both the lining and outer layers. The individual panels were sewn with the straight edge joining an angled edge for stability of the fabric.

To construct the body of the garment, I layered the lining and the outer layer and sewed the pieces together at the main center seams using a running stitch in linen thread. The wool outer layer was then folded open and stitched down with rows of running stitches of silk thread. The interior details of garments are rarely seen in contemporary images, however, the St. John Altarpiece by Rogier Van der Weyden from 1455 (although several decades later than the intended date of this garment) shows the inside of a garment with the outer layer visible at the center back seam. The seams from the pieces of the lining show that sections of the lining were sewn together before being connected to the outer layer.

There are silk facings around the armholes at the shoulder and on the buttonhole side of the wrist opening. The silk was cut on the straight of the grain. The silk facing on the sleeve was attached after the hem was completed as seen on textile No. 64 in Textiles and Clothing and was attached using running stitches and an overlapping hemstitch.

I chose to decorate the cuffs with several rows of silk running stitch to achieve the same effect as seen in the image below.

Buttons are made from circles of wool that were sewn with wide running stitches and then gathered into small balls. The edges of the circle are folded into the center creating a stuffing that bulks up the button. A thread shank is formed when the buttons are attached to the very edge of the garment. Buttons are used at the sleeve openings as well as the neck opening. (I will post a detailed tutorial about button making in a future post!)

Bibliography

Luisa Cogliati Arano, The Medieval Health Handbook: Tacuinum Sanitatis, (New York: George Braziller) 1976.

Jack Banyard “Praguestyle Houpelande,” accessed December 2012, http://www.chesholme.com/~jack/prague-houp/.

I. Marc Carlson, “Some Clothing of the Middle Ages,” accessed November 2012, http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/blois.html.

Chroniquesde France ou de St Denis, last quarter 14th century, Royal 20 C VII, British Library, London, accessed September 2012, http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=8466&CollID=16&NStart=200307.

Elisabeth Crowfoot, Frances Pritchard, and Kay Staniland,Medieval Finds from Excavations in London : 4 Textiles and Clothing 1150-1450, (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press) 2002.

Anne D. Hedeman, The Royal Image: Illustrations of the GrandeChroniques de France, 1274-1422, (Berkeley: University of California Press) 1991, accessed February 2013, http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft8k4008jd/.

Martina Hrib and Martin Hrib, “Historicke kostymy a strihy,” accessed December 2012, http://www.kostym.cz.

Tasha Dandelion Kelly, “Cut to pieces by a determined tailor: The piecing of the Charles deBlois pourpoint,” La cotte simple, accessed September 2012, http://cottesimple.com/articles/cut-to-pieces/.

Ian Monk, trans.,The Hunting Book of Gaston Phébus, (Dallas: Hackberry Press) 2002.

Stella Mary Newton, Fashion in the Age of the Black Prince, (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press) 2002.

Rogier Van der Weyden, St-John Altarpiece, 1455, Oil on oak panel, 77 cm x 48 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

Cynthia Virtue, “ATheory on Construction of the Houppelande,’ accessed September, 2012, http://www.virtue.to/articles/circle_houp.html.

Link to Complete documentation in PDF: